A little more than a month ago, I had several calls with a few DeepEval users and noticed a clear divide — those who were happy with the out-of-the-box metrics and those who weren’t.

For context, DeepEval is an open-source LLM evaluation framework I’ve been working on for the past year, and all of its LLM evaluation metrics uses LLM-as-a-judge. It’s grown to nearly half a million monthly downloads and close to 5,000 GitHub stars. With over 800k daily evaluations ran, engineers nowadays use it to unit-testing LLM applications such as RAG pipelines, agents, and chatbots.

The users who weren’t satisfied with our metrics had a simple reason: the metrics didn’t fit their use case and they weren’t deterministic enough since they were all evaluated using LLM-as-a-judge. That’s a real problem because the whole point of DeepEval is to eliminate the need for engineers to build their own evaluation metrics and pipelines. If our built-in metrics aren’t usable and people have to go through that effort anyway, then we have no reason to exist.

The more users I talked to, the more I saw codebases filled with hundreds of lines of prompts and logic just to tweak the metrics to be more tailored and deterministic. It was clear that users weren’t just customizing — they were compensating for gaps in what we provided.

This raised an important question: How can we make DeepEval’s built-in metrics flexible and deterministic enough that fewer teams feel the need to roll their own?

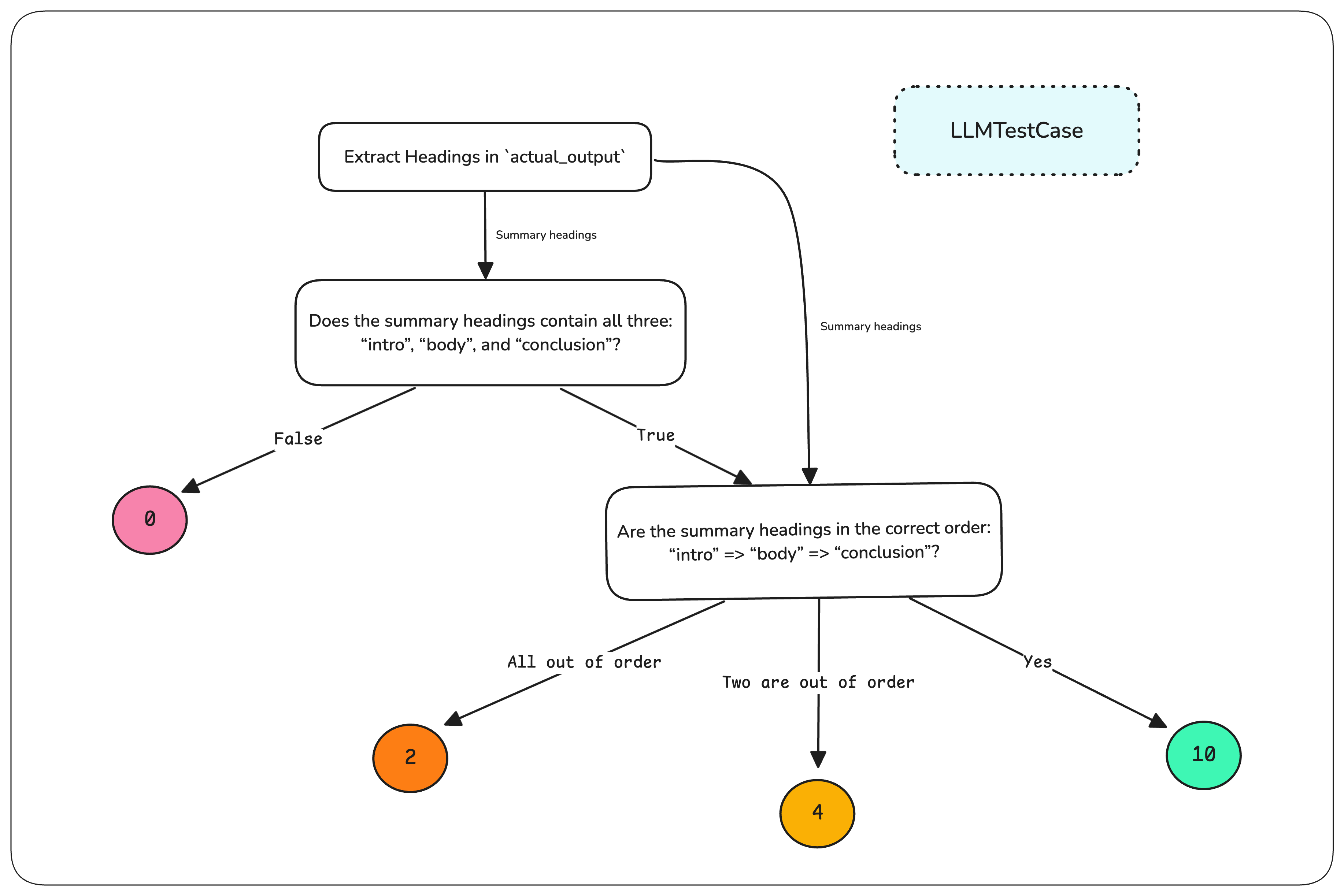

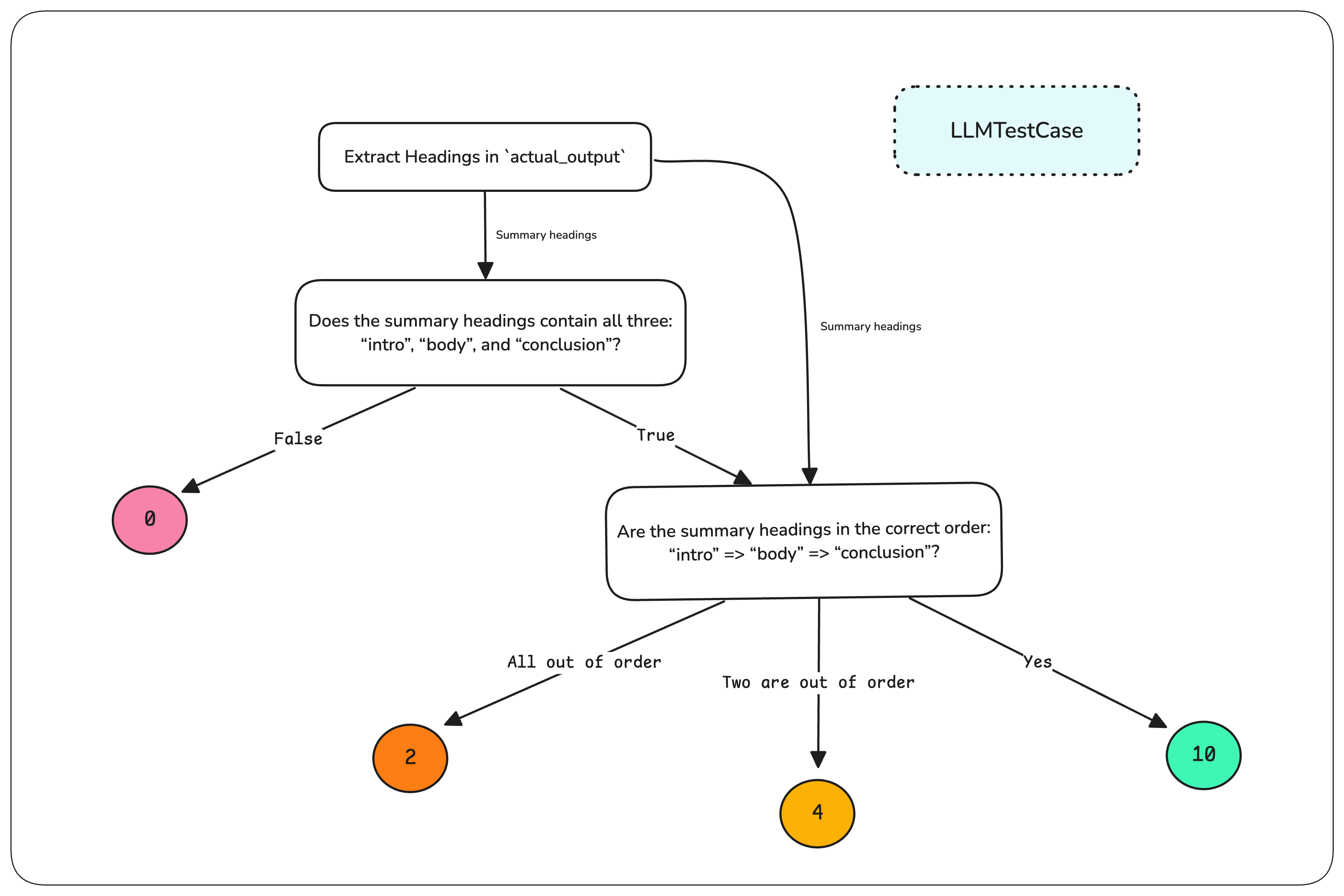

Spoiler alert - the solution looks something like this:

The Problem With Custom Metrics

To set the stage better, DeepEval’s default metrics are metrics such as contextual recall, answer relevancy, answer correctness, etc. where the criteria was more general and (relatively) stable. I say stable, because these metrics were mostly based on the question-answer-generation (QAG) technique. Since QAG constrains verdicts to a binary “yes” or “no” for close-ended questions, there’s very little room for stochasticity.

And no, we're not using statistical scorers for LLM evaluation metrics, and you can learn why in this separate article.

I’d also argue that, metrics like answer relevancy are inherently broad. It’s difficult to define relevancy in absolute terms, but as long as the metric provides a reasonable explanation, most people are willing to accept it. Another reason these metrics worked well is that they had clear and straightforward equations behind them. Whether someone liked a metric or not usually came down to whether they agreed with the algorithm used to calculate it.

For example, the contextual recall metric mentioned earlier assess a RAG pipeline’s retriever — it determines for a given input to your LLM application, whether the text chunks your retriever has retrieved is sufficient to produce the ideal expected LLM output. The algorithm was simple and intuitive:

Extract all attributes found in the expected output using an LLM-judge

For each extracted attribute, use an LLM-judge to determine whether it can be inferred from the retrieval context, which is a list of text nodes. This uses QAG, where the determination will be either “yes” or “no” for each extracted attribute.

The final contextual recall score was the proportion of “yes”s in total.

It was easy to understand and made intuitive sense — after all, this is exactly how recall should work. And because the LLM-judge was constrained to binary responses in step 2, the evaluation remained mostly stable for any given test case.

But the problem came when we started looking at evaluation metrics that involved custom criteria and quite frankly, I also didn’t believe our default metrics are well-rounded enough for use case specific evaluation.

You see, when I talk about custom criteria, I don’t mean something simple like:

“Determine if the LLM output is a good summary of the expected output.”

That’s relatively straightforward. What I mean are criteria like:

“Check if the output is in markdown format. If it is, verify that all summary headings are present. If they are, confirm they are in the correct order. Then, assess the quality of the summary itself.”

This kind of evaluation is fundamentally different. It’s no longer just about determining quality — it’s about enforcing a multi-step process with conditional logic, each step introducing new layers of complexity.

Internally, we started calling simpler criteria like “is this a good summary?” toy criteria. These cases didn’t require true deterministic evaluation, and we already had GEval to support them, a SOTA metric to score custom criteria through CoT prompting via a form-filling paradigm. Sure, users could tweak their criteria’s language to make the metric more or less strict, but when you have a clear use case like summarization and don’t have thousands of test cases to establish statistical significance, you need deterministic evaluation. For most users, this was a deal-breaker, and so in these cases, it’s not enough to rely on loose, subjective assessments — the evaluation needs to produce consistent, reliable scores that teams can trust to reflect real performance.

This brings us back to the horrifying codebases we saw — hundreds of lines dedicated to tweaking and shaping evaluation logic just to make the metrics work for specific use cases.

The Eval Platform for AI Quality & Observability

Confident AI is the leading platform to evaluate AI apps on the cloud, powered by DeepEval.